Deng Xiaoping

- This is a Chinese name; the family name is Deng.

| Deng Xiaoping | |

Deng Xiaoping in 1979 |

|

|

Paramount leader

|

|

|---|---|

| In office 22 December 1978 - 12 October 1992 (13 years, 295 days) |

|

| President | Li Xiannian Yang Shangkun |

| Premier | Hua Guofeng Zhao Ziyang Li Peng |

| Vice President | Ulanhu Wang Zhen |

| Vice Premier | Himself Wan Li Yao Yilin |

| Preceded by | Hua Guofeng |

| Succeeded by | Jiang Zemin |

|

Chairman of the Central Military Commission of CCP

|

|

| In office 28 June 1981 - 9 November 1989 |

|

| Preceded by | Hua Guofeng |

| Succeeded by | Jiang Zemin |

|

Chairman of the CPPCC

|

|

| In office 8 March 1978 - 17 June 1983 |

|

| Preceded by | Zhou Enlai vacant (1976-1978) |

| Succeeded by | Deng Yingchao |

|

First Vice Premier of the People's Republic of China

|

|

| In office 17 January 1975 - 18 June 1983 |

|

| Premier | Zhou Enlai Hua Guofeng Zhao Ziyang |

| Preceded by | Lin Biao |

| Succeeded by | Wan Li |

|

General Secretary of the Central Secretariat of CPC

|

|

| In office September 1956 - March 1967 |

|

| Preceded by | Zhang Wentian (in 1943) |

| Succeeded by | Hu Yaobang |

|

|

|

| Born | 22 August 1904 Guang'an, Sichuan, Empire of the Great Qing of China |

| Died | 19 February 1997 (aged 92) Beijing, People's Republic of China |

| Nationality | Chinese |

| Political party | Communist Party of China |

| Spouse(s) | Zhang Xiyuan (张锡瑗) (1928-1929) Jin Weiying (金维映) (1931-1939) Zhuo Lin (1939-1997) |

| Children | Deng Lin Deng Pufang Deng Nan Deng Rong Deng Zhifang |

| Signature |  |

| Deng Xiaoping | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 鄧小平 | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 邓小平 | ||||||||

|

|||||||||

Deng Xiaoping listen (simplified Chinese: 邓小平; traditional Chinese: 鄧小平; pinyin: Dèng Xiǎopíng; 22 August 1904 – 19 February 1997) was a Chinese politician, statesman, theorist, and diplomat.[1] As leader of the Communist Party of China, Deng was a reformer who led China towards a market economy. While Deng never held office as the head of state, head of government or General Secretary of the Communist Party of China (historically the highest position in Communist China), he nonetheless served as the paramount leader of the People's Republic of China from 1978 to the early 1990s.

Born into a farming background in Guang'an, Sichuan, Empire of the Great Qing of China Deng studied and worked in France in the 1920s, where he came under the influence of Marxism. He joined the Communist Party of China in 1923. Upon his return to China he worked as a political commissar in rural regions and was considered a "revolutionary veteran" of the Long March.[2] Following the founding of the People's Republic of China in 1949, Deng worked in Tibet and other southwestern regions to consolidate Communist control. He was also instrumental in China's economic reconstruction following the Great Leap Forward in the early 1960s. His economic policies were at odds with the political ideologies of Chairman Mao Zedong. As a result, he was purged twice during the Cultural Revolution but regained prominence in 1978 by outmaneuvering Mao's chosen successor, Hua Guofeng.

Inheriting a country wrought with social and institutional woes resulting from the Cultural Revolution and other mass political movements of the Mao era, Deng became the core of the "second generation" of Chinese leadership. He is considered "the architect" of a new brand of socialist thinking, having developed Socialism with Chinese characteristics and led Chinese economic reform through a synthesis of theories that became known as the "socialist market economy". Deng opened China to foreign investment, the global market, and limited private competition. He is generally credited with advancing China into one of the fastest growing economies in the world for over thirty years and vastly raising the standard of living of hundreds of millions of Chinese.[3]

Contents

|

Biography

Early life and family

Deng Xiansheng was born into an ethnically Hakka Han family in Paifang village (牌坊村), Xiexin township (协兴镇), Guang'an County in Sichuan province,[4][5] approximately 160 km from Chongqing (formerly spelled Chungking). Deng's ancestors can be traced back to Meixian County in Guangdong Province,[5] a prominent ancestral area for the Hakka people, and had been settled in Sichuan for several generations.[6]

Deng's father, Deng Wenming, was a middle-level landowner and had studied at the University of Law and Political Science in Chengdu. His mother, surnamed Dan, died early in Deng's life, leaving Xiaoping, his three brothers and three sisters.[7] At the age of five, Xiaoping was sent to a traditional Chinese-style private primary school, followed by a more modern primary school at the age of seven.

Deng's first wife, one of his schoolmates from Moscow, died when she was 24, a few days after giving birth to Deng's first child, a baby girl, who also died. His second wife, Jin Weiying, left him after Deng came under political attack in 1933. His third wife, Zhuo Lin, was the daughter of an industrialist in Yunnan Province. She became a member of the Communist Party in 1938, and married Deng a year later in front of Mao's cave dwelling in Yan'an. They had five children: three daughters (Deng Lin, Deng Nan and Deng Rong) and two sons (Deng Pufang and Deng Zhifang).

Education and early career

In the summer of 1919, Deng Xiaoping graduated from the Chongqing Preparatory School. He and 80 schoolmates travelled by ship to France (traveling steerage) to participate in (the Mouvement Travail-Études, a work-study program in which 4,000 Chinese would participate by 1927). Deng, the youngest of all the Chinese students in the group, had just turned 15.[8] Wu Yuzhang, local leader of the Mouvement Travail-Études in Chongqing, enrolled Deng and his paternal uncle, Deng Shaosheng, in the program. Deng's father strongly supported his son's participation in the work-study abroad program.[9] The night before his departure, Deng's father took his son aside and asked him what he hoped to learn in France. He repeated the words he had learned from his teachers: "To learn knowledge and truth from the West in order to save China." Deng Xiaoping had been taught that China was weak and poor, and that the Chinese people must have a modern, Western education to save their country.[10]

After studying French for a year,[11] Deng departed with other Chinese students from Shanghai. On October 19, 1920 they arrived in Marseille, then traveled to Paris by train. He briefly attended middle schools in Bayeux and Châtillon, but he spent most of his time in France working; first at the Le Creusot Iron and Steel plant in central France, then as a fitter in the Renault factory in the Paris suburb of Billancourt, a fireman on a locomotive and a kitchenhand. He barely earned enough to survive. Many of these jobs had very harsh and dangerous working conditions, with workers frequently being injured. Deng would later claim that it was here where he got an initial feel for the evils of capitalist society.

Under the influence of older Chinese students in France (Zhao Shiyan, Zhou Enlai among others), Deng began to study Marxism and engaged in political dissemination work. In 1921 he joined the Chinese Communist Youth League in Europe. In the second half of 1924 he joined the Chinese Communist Party and became one of the leading members of the General Branch of the Youth League in Europe. In 1926 Deng traveled to the Soviet Union and studied at Moscow Sun Yat-sen University, where one of his classmates was Chiang Ching-kuo.[12] Deng returned to China in 1927.

In 1928 Deng led the Baise Uprising in Guangxi province against the Kuomintang (KMT) government. The uprising failed and Deng went to the Central Soviet Area in Jiangxi province.

Deng served as General Secretary of the Secretariat of the Communist Party and was a veteran of the Long March. While acting as political commissar for Liu Bocheng, he organized several important military campaigns during the war with Japan and during the Civil War against the Kuomintang. In late November 1948, Deng led the final assault on Kuomintang forces, who were under the direct command of Chiang Kai-shek in Sichuan. Chongqing fell to the PLA on 1 December and Deng was appointed mayor and political commissar. Chiang, who had moved his headquarters to Chongqing in mid-November, fled to the provincial capital of Chengdu. It was the last mainland Chinese city to be held by the KMT, and fell on 10 December. Chiang fled to Taiwan on the same day. When the PRC was founded in 1949 Deng was sent to oversee issues in the Southwestern Region, and acted as its First Secretary.

Political rise

Policymaker following the Great Leap Forward

As a supporter of Mao Zedong, Mao appointed Deng to several important posts in the new government.

After officially supporting Mao Zedong in his Anti-Rightist Campaign of 1957, Deng became General Secretary of the Secretariat and ran the country's daily affairs with then-President Liu Shaoqi. Having failed to advance the “social productive forces” in the Great Leap Forward through the “communist wind” and the “exaggeration wind”, Liu and Deng moved from an “ultra-leftist” approach to a “pragmatic” or right opportunist approach.

In the rural areas, peasants were allowed larger private plots and given permission to sell their outputs on the free market, diverting peasants’ labour effort away from the collective work. The collective work itself was partially privatised as a result of the “contracting production to the family” policy. This new partial privatisation led to rising inequality among peasants as well as growing corruption among the rural cadres. In the cities, the industrial sector was reorganised to concentrate power and authority in the hands of managerial and technical experts. Bonuses and piece rates were widely introduced to promote economic efficiency, leading to rising economic and social inequality.

Deng and Liu used growing disenchantment with Great Leap Forward to gain influence within the CCP. They embarked on economic reforms that bolstered their prestige among the party technocrats and apparatus bureaucrats. Deng and Liu advocated more rightist policies, as opposed to Mao's leftist ideas.

In 1961, at the Guangzhou conference, Deng uttered what is perhaps his most famous quotation: "I don't care if it's a white cat or a black cat. It's a good cat so long as it catches mice."[13] This was interpreted to mean that being productive in life is more important than whether one follows a communist or capitalist ideology.

Two purges

Mao feared that the right-wing politics of Deng and Liu could lead to restoration of capitalism and end the Chinese Revolution.[14] For this and other reasons, Mao launched the Cultural Revolution in 1966, during which Deng fell out of favor and was forced to retire from all his offices. He was sent to the Xinjian County Tractor Factory in rural Jiangxi province to work as a regular worker. While there Deng spent his spare time writing. He was purged nationally, but to a lesser scale than Liu Shaoqi.

During the Cultural Revolution, Deng Xiaoping and his family were targeted by Red Guards. Red Guards imprisoned Deng's son, Deng Pufang. Deng Pufang was tortured and forced out of the window of a four-story building, becoming a paraplegic.

Nonetheless, when Maoist rebels were defeated, and after Lin Biao launched an abortive coup before being killed in an air crash, Deng Xiaoping (who had led a large field army during the civil war) became the most influential of the remaining army leaders.[14] When Premier Zhou Enlai fell ill with cancer, Deng Xiaoping became Zhou's choice for a successor, and Zhou was able to convince Mao to bring Deng Xiaoping back into politics in 1974 as First Vice-Premier, in practice running daily affairs. Deng focused on reconstructing the country's economy and stressed unity as the first step to raising production. He remained careful, however, to avoid contradicting Maoist ideology, at least on paper.

The Cultural Revolution was not yet over, and a radical leftist political group known as the Gang of Four, led by Mao's wife Jiang Qing, competed for power within the Communist Party. The Gang saw Deng as their greatest challenge to power.[15] Mao, too, was suspicious that Deng would destroy the positive reputation of the Cultural Revolution, which Mao considered one of his greatest policy initiatives. Beginning in late 1975, Deng was asked to draw up a series of self-criticisms. Although Deng admitted to having taken an "inappropriate ideological perspective" while dealing with state and party affairs, he was reluctant to admit that his policies were wrong in essence. Deng's antagonism with the Gang of Four became increasingly clear, and Mao seemed to swing in the Gang's favour. Mao refused to accept Deng's self-criticisms and asked the party's Central Committee to "discuss Deng's mistakes thoroughly".

Zhou Enlai died in January 1976, to an outpouring of national grief. Zhou was a very important figure in Deng's political life, and his death eroded the little support within the Party's Central Committee that Deng had left. After delivering Zhou's official eulogy at the state funeral, the Gang of Four, with Mao's permission, began the so-called Criticize Deng and Oppose the Rehabilitation of Right-leaning Elements campaign. Hua Guofeng, not Deng, was selected to become Zhou's successor. On 2 February, the Central Committee issued a Top-priority Directive, officially transferring Deng to work on "external affairs", removing Deng from the party's power apparatus. Deng stayed at home for several months, awaiting his fate. The political turmoil brought the economic progress Deng had laboured for in the past year to a halt. On 3 March, Mao issued a directive reaffirming the legitimacy of the Cultural Revolution and specifically pointed to Deng as an internal, rather than external, problem. This was followed by a Central Committee directive issued to all local party organs to study Mao's directive and criticize Deng.

Deng's political fortunes were dealt another blow following Qingming Festival, when the mass mourning of Premier Zhou on the traditional Chinese holiday sparked the Tiananmen Incident of 1976, an event the Gang of Four branded as counter-revolutionary and threatening to their power. Furthermore, the Gang deemed Deng the mastermind behind the incident, and Mao himself wrote that "the nature of things has changed".[16] This prompted Mao's decision to remove Deng from all leadership positions whilst retaining his party membership.

Re-emergence

Deng gradually emerged as the de-facto leader of China following Mao's death in 1976. Prior to Mao's death, the only governmental position he held was that of First Vice-Premier of the State Council.[17] By carefully mobilizing his supporters within the Chinese Communist Party, Deng was able to outmaneuver Mao's appointed successor Hua Guofeng, who had pardoned him, then oust Hua from his top leadership positions by 1980. In contrast to previous leadership changes, Deng allowed Hua to retain membership in the Central Committee and quietly retire, helping to set the precedent that losing a high-level leadership struggle would not result in physical harm.

Deng repudiated the Cultural Revolution and, in 1977, launched the "Beijing Spring", which allowed open criticism of the excesses and suffering that had occurred during the period. Meanwhile, he was the impetus for the abolishion of the class background system. Under this system, the CCP put up employment barriers to Chinese deemed to be associated with the former landlord class; its removal allowed Chinese capitalists to join the Communist Party.

Deng gradually outmaneuvered his political opponents. By encouraging public criticism of the Cultural Revolution, he weakened the position of those who owed their political positions to that event, while strengthening the position of those like himself who had been purged during that time. Deng also received a great deal of popular support. As Deng gradually consolidated control over the CCP, Hua was replaced by Zhao Ziyang as premier in 1980, and by Hu Yaobang as party chief in 1981. Deng remained the most influential of the CCP cadre, although after 1987 his only official posts were as chairman of the state and Communist Party Central Military Commissions.

Originally, the president was conceived of as a figurehead of state, with actual state power resting in the hands of the premier and the party chief, both offices being conceived of as held by separate people in order to prevent a cult of personality from forming (as it did in the case of Mao); the party would develop policy, whereas the state would execute it.

Deng's elevation to China's new number-one figure meant that the historical and ideological questions around Mao Zedong had to be addressed properly. Because Deng wished to pursue deep reforms, it was not possible for him to continue Mao's hard-line "class struggle" policies and mass public campaigns. In 1982 the Central Committee of the Communist Party released a document entitled On the Various Historical Issues since the Founding of the People's Republic of China. Mao retained his status as a "great Marxist, proletarian revolutionary, militarist, and general", and the undisputed founder and pioneer of the country and the People's Liberation Army. "His accomplishments must be considered before his mistakes", the document declared. Deng personally commented that Mao was "seven parts good, three parts bad." The document also steered the prime responsibility of the Cultural Revolution away from Mao (although it did state that "Mao mistakenly began the Cultural Revolution") to the "counter-revolutionary cliques" of the Gang of Four and Lin Biao.

Opening up

Under Deng's direction, relations with the West improved remarkably. Deng traveled abroad and had a series of amicable meetings with western leaders, and became the first Chinese leader to visit the United States in 1979, meeting with President Carter at the White House. Shortly before this meeting, the U.S. had broken diplomatic relations with the Republic of China (Taiwan) and established them with the People's Republic of China (PRC).

Sino-Japanese relations also improved significantly. Deng used Japan as an example of a rapidly progressing power that set a good example for China economically.

Another achievement was the agreement signed by United Kingdom and China on 19 December 1984 (Sino-British Joint Declaration) under which Hong Kong was to be handed over to the PRC in 1997. With the 99-year British lease on the New Territories expiring, Deng agreed that the PRC would not interfere with Hong Kong's capitalist system for 50 years. A similar agreement was signed with Portugal for the return of Macau. Dubbed "one country, two systems", this approach has been touted by the PRC as a potential framework within which Taiwan could be reunited with the Mainland in the future.

In October 1987, at the Plenary Session of the National People's Congress, Deng Xiaoping was re-elected as Chairman of Central Military Commission, but he resigned as Chairman of the Central Advisory Commission and he was succeeded by Chen Yun. He continued to chair and developed the reform and opening up as the main policy, put forward the three-step suitable for China's economic development strategy within 70 years: the first step, to double the 1980 GNP and ensure that the people have enough food and clothing, was attained by the end of the 1980s; second step, to quadruple the 1980 GNP by the end of the 20th century, was achieved in 1995 ahead of schedule; the third step, to increase per capita GNP to the level of the medium-developed countries by 2050, at which point, the Chinese people will be fairly well-off and modernization will be basically realized.

Deng, however, did little to improve relations with the Soviet Union, continuing to adhere to the Maoist line of the Sino-Soviet split era that the Soviet Union was a superpower equally as "hegemonist" as the United States, but even more threatening to China because of its geographic proximity.

Economic reforms

Improving relations with the outside world was the second of two important philosophical shifts outlined in Deng's program of reform termed Gaige Kaifang (lit. Reforms and Openness). The domestic social, political, and most notably, economic systems would undergo significant changes during Deng's time as leader. The goals of Deng's reforms were summed up by the Four Modernizations, those of agriculture, industry, science and technology and the military.

The strategy for achieving these aims of becoming a modern, industrial nation was the socialist market economy. Deng argued that China was in the primary stage of socialism and that the duty of the party was to perfect so-called "socialism with Chinese characteristics", and "seek truth from facts". (This somewhat resembles the Leninist theoretical justification of the NEP in the 20s, which argued that Russia hadn't gone deeply enough in to the capitalist phase and therefore needed limited capitalism in order to fully evolve its means of production) This interpretation of Maoism reduced the role of ideology in economic decision-making and deciding policies of proven effectiveness. Downgrading communitarian values but not necessarily the ideology of Marxism-Leninism himself, Deng emphasized that "socialism does not mean shared poverty". His theoretical justification for allowing market forces was given as such:

Planning and market forces are not the essential difference between socialism and capitalism. A planned economy is not the definition of socialism, because there is planning under capitalism; the market economy happens under socialism, too. Planning and market forces are both ways of controlling economic activity."[18]

Unlike Hua Guofeng, Deng believed that no policy should be rejected outright simply because it was not associated with Mao. Unlike more conservative leaders such as Chen Yun, Deng did not object to policies on the grounds that they were similar to ones which were found in capitalist nations.

This political flexibility towards the foundations of socialism is strongly supported by quotes such as:

We mustn't fear to adopt the advanced management methods applied in capitalist countries (...) The very essence of socialism is the liberation and development of the productive systems (...) Socialism and market economy are not incompatible (...) We should be concerned about right-wing deviations, but most of all, we must be concerned about left-wing deviations.[19]

Although Deng provided the theoretical background and the political support to allow economic reform to occur, it is in general consensus amongst historians that few of the economic reforms that Deng introduced were originated by Deng himself. Premier Zhou Enlai, for example, pioneered the Four Modernizations years before Deng. In addition, many reforms would be introduced by local leaders, often not sanctioned by central government directives. If successful and promising, these reforms would be adopted by larger and larger areas and ultimately introduced nationally. An often cited example is the household-responsibility system, which was first secretly implemented by a poor rural village at the risk of being convicted as "counter-revolutionary." This experiment proved very successful.[20] Deng openly supported it and it was later adopted nationally. Many other reforms were influenced by the experiences of the East Asian Tigers.

This is in sharp contrast to the pattern in the perestroika undertaken by Mikhail Gorbachev in which most of the major reforms were originated by Gorbachev himself. The bottom-up approach of the Deng reforms, in contrast to the top-down approach of perestroika, was likely a key factor in the success of the former.[21]

Deng's reforms actually included the introduction of planned, centralized management of the macro-economy by technically proficient bureaucrats, abandoning Mao's mass campaign style of economic construction. However, unlike the Soviet model, management was indirect through market mechanisms. Deng sustained Mao's legacy to the extent that he stressed the primacy of agricultural output and encouraged a significant decentralization of decision making in the rural economy teams and individual peasant households. At the local level, material incentives, rather than political appeals, were to be used to motivate the labor force, including allowing peasants to earn extra income by selling the produce of their private plots at free market.

In the main move toward market allocation, local municipalities and provinces were allowed to invest in industries that they considered most profitable, which encouraged investment in light manufacturing. Thus, Deng's reforms shifted China's development strategy to an emphasis on light industry and export-led growth. Light industrial output was vital for a developing country coming from a low capital base. With the short gestation period, low capital requirements, and high foreign-exchange export earnings, revenues generated by light manufacturing were able to be reinvested in more technologically-advanced production and further capital expenditures and investments.

However, in sharp contrast to the similar but much less successful reforms in Yugoslavia and Hungary, these investments were not government mandated. The capital invested in heavy industry largely came from the banking system, and most of that capital came from consumer deposits. One of the first items of the Deng reforms was to prevent reallocation of profits except through taxation or through the banking system; hence, the reallocation in state-owned industries was somewhat indirect, thus making them more or less independent from government interference. In short, Deng's reforms sparked an industrial revolution in China.[22]

These reforms were a reversal of the Maoist policy of economic self-reliance. China decided to accelerate the modernization process by stepping up the volume of foreign trade, especially the purchase of machinery from Japan and the West. By participating in such export-led growth, China was able to step up the Four Modernizations by attaining certain foreign funds, market, advanced technologies and management experiences, thus accelerating its economic development. Deng attracted foreign companies to a series of Special Economic Zones, where foreign investment and market liberalization were encouraged.

The reforms centered on improving labor productivity as well. New material incentives and bonus systems were introduced. Rural markets selling peasants' homegrown products and the surplus products of communes were revived. Not only did rural markets increase agricultural output, they stimulated industrial development as well. With peasants able to sell surplus agricultural yields on the open market, domestic consumption stimulated industrialization as well and also created political support for more difficult economic reforms.

There are some parallels between Deng's market socialism especially in the early stages, and Lenin's New Economic Policy as well as those of Bukharin's economic policies, in that both foresaw a role for private entrepreneurs and markets based on trade and pricing rather than central planning. An interesting anecdote on this note is the first meeting between Deng and Armand Hammer. Deng pressed the industrialist and former investor in Lenin's Soviet Union for as much information on the NEP as possible.

Role in the Tiananmen Square protests

The Tiananmen Square protests of 1989 culminating in the June Fourth Incident were a series of demonstrations in and near Tiananmen Square in the People's Republic of China (PRC) between 15 April and 4 June 1989. Many socialist governments collapsed during the same year.

The protests were sparked by the death of Hu Yaobang, a reformist official backed by Deng Xiaoping and ousted by his enemies. Many people were dissatisfied with the party's slow response and relatively subdued funerary arrangements. Public mourning began on the streets of Beijing and elsewhere. In Beijing this was centred on the Monument to the People's Heroes in Tiananmen Square. The mourning became a public conduit for anger against perceived nepotism in the government, the unfair dismissal and early death of Hu, and the behind-the-scenes role of the "old men". By the eve of Yaobang's funeral, the demonstration had reached 100,000 people on Tiananmen Square. While the protests lacked a unified cause or leadership, participants raised the issue of corruption within the government and some voiced calls for economic liberalization[23] and democratic reform[23] within the structure of the government while others called for a less authoritarian and less centralized form of socialism.[24][25]

During demonstrations, Deng Xiaoping's pro-market ally, General Secretary Zhao Ziyang, supported demonstrators and distanced himself from the Politburo. Martial law was declared on 20 May by the socialist hardliner Li Peng, but no action was taken until 4 June. The movement lasted seven weeks. Soldiers and tanks from the 27th and 28th Armies of the People's Liberation Army were sent to take control of the city on 4 June. Many ordinary people in Beijing believed that Deng Xiaoping had ordered the intervention, but political analysts do not know who was actually behind the order.[26] However, Deng's daughter defends the actions that occurred as a collective decision by the party leadership.[27]

To purge sympathizers of Tiananmen demonstrators, the Communist Party initiated a one and half year long program similar to Anti-Rightist Movement. It aimed to deal "strictly with those inside the party with serious tendencies toward bourgeois liberalization" and more than 30,000 communist officers were deployed to the task.[28]

Zhao was placed under house arrest by socialist hardliners and Deng Xiaoping himself was forced to make concessions to anti-reform communists.[26] He soon declared that "the entire imperialist Western world plans to make all socialist countries discard the socialist road and then bring them under the monopoly of international capital and onto the capitalist road". A few months later he said that the "United States was too deeply involved" in the student movement, referring to foreign reporters who had given financial aid to the student leaders and later helped them escape to various Western countries, primarily the United States through Hong Kong and Taiwan.[26]

Although at first he made concessions to the socialist hardliners, he soon resumed his reforms after his 1992 southern tour. After his tour, he was able to stop the attacks of the socialist hardliners on the reforms through their "named capitalist or socialist?" campaign.[29]

Deng Xiaoping privately told the Canadian Prime Minister that factions of the Communist Party could have grabbed army units and the country had risked a civil war.[28] Two years later, Deng Xiaoping endorsed Zhu Rongji, a Shanghai Mayor, as a vice-premier candidate. Zhu Rongji had refused to declare martial law in Shanghai during the demonstrations even though socialist hardliners had pressured him.[26]

After resignation and the 1992 southern tour

Officially, Deng decided to retire from top positions when he stepped down as Chairman of the Central Military Commission in 1989, and retired from the political scene in 1992. China, however, was still in the era of Deng Xiaoping. He continued to be widely regarded as the "paramount leader" of the country, believed to have backroom control. Deng was recognized officially as "The chief architect of China's economic reforms and China's socialist modernization". To the Communist Party, he was believed to have set a good example for communist cadres who refused to retire at old age. He broke earlier conventions of holding offices for life. He was often referred to as simply Comrade Xiaoping, with no title attached.

Because of the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989, Deng's power had been significantly weakened and there was a growing formalist faction opposed to Deng's reforms within the Communist Party. To reassert his economic agenda, in the spring of 1992, Deng made his famous southern tour of China, visiting Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Zhuhai and spending the New Year in Shanghai, in reality using his travels as a method of reasserting his economic policy after his retirement from office. On his tour, Deng made various speeches and generated large local support for his reformist platform. He stressed the importance of economic construction in China, and criticized those who were against further economic and openness reforms. Although there is debate on whether or not Deng actually said it,[30] his perceived catchphrase, "To get rich is glorious", unleashed a wave of personal entrepreneurship that continues to drive China's economy today. He stated that the "leftist" elements of Chinese society were much more dangerous than "rightist" ones. Deng was instrumental in the opening of Shanghai's Pudong New Area, revitalizing the city as China's economic hub.

His southern tour was initially ignored by the Beijing and national media, which were then under the control of Deng's political rivals. Jiang Zemin showed little support. Challenging their media control, Shanghai's Liberation Daily newspaper published several articles supporting reforms authored by "Huangfu Ping", which quickly gained support amongst local officials and populace. Deng's new wave of policy rhetoric gave way to a new political storm between factions in the Politburo. President Jiang eventually sided with Deng, and the national media finally reported Deng's southern tour several months after it occurred. Observers suggest that Jiang's submission to Deng's policies had solidified his position as Deng's heir apparent. Behind the scenes, Deng's southern tour aided his reformist allies' climb to the apex of national power, and permanently changed China's direction toward economic development. In addition, the eventual outcome of the southern tour proved that Deng was still the most powerful man in China.[31]

Deng's insistence on economic openness aided in the phenomenal growth levels of the coastal areas, especially the "Golden Triangle" region surrounding Shanghai. Deng reiterated that "some areas must get rich before others", and asserted that the wealth from coastal regions will eventually be transferred to aid economic construction inland. The theory, however, faced numerous challenges when put into practice, as provincial governments moved to protect their own interests. The policy contributed to a widening wealth disparity between the affluent coast and the underdeveloped hinterlands.

Death and reaction

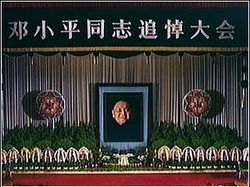

After being disconnected from life supporting machines, Deng Xiaoping died on 19 February 1997, at age 92 from a lung infection and Parkinson's disease, but his influence continued. Even though Jiang Zemin was in firm control, government policies maintained Deng's political and economic philosophies. Officially, Deng was eulogized as a "great Marxist, great Proletarian Revolutionary, statesman, military strategist, and diplomat; one of the main leaders of the Communist Party of China, the People's Liberation Army of China, and the People's Republic of China; The great architect of China's socialist opening-up and modernized construction; the founder of Deng Xiaoping Theory".[32]

Although the public was largely prepared for Deng's death, as rumors had been circulating for a long time, the death of Deng was followed by the greatest publicly sanctioned display of grief for any Chinese leader since Mao Zedong. However, in contrast, Deng's death in the media was announced without any titles attached (Mao was called the Great Leader and Teacher, Deng was simply "Comrade"), or any emotional overtones from the news anchors that delivered the message.

At 10 A.M. on the morning of 24 February, people were asked by Premier Li Peng to pause in silence for three minutes. The nation's flags flew at half-staff for over a week. The nationally televised funeral, which was a simple and relatively private affair attended by the country's leaders and Deng's family, was broadcast on all cable channels. Jiang's tearful eulogy to the late reformist leader declared, "The Chinese people love, thank, mourn and cherish the memory of Comrade Deng Xiaoping because he devoted his life-long energies to the Chinese people, performed immortal feats for the independence and liberation of the Chinese nation." Jiang vowed to continue Deng's policies.

After the funeral, his organs donated to medical research, the remains were cremated, and his ashes were subsequently scattered at sea, according to his wishes. For the next two weeks, Chinese state media ran news stories and documentaries related to Deng's life and death, with the regular 7 p.m. National News program in the evening lasting almost two hours over the regular broadcast time.

Certain segments of the Chinese population, notably the modern Maoists and radical reformers (the far left and the far right), had negative views on Deng. In the year that followed, songs like "Story of Spring" by Dong Wenhua, which were created in Deng's honour shortly after Deng's southern tour in 1992, once again were widely played.

There was a significant amount of international reaction to Deng's death: UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan said Deng was to be remembered "in the international community at large as a primary architect of China's modernization and dramatic economic development". French President Jacques Chirac said "In the course of this century, few men have, as much as Deng Xiaoping, led a vast human community through such profound and determining changes"; British Prime Minister John Major commented about Deng's key role in the return of Hong Kong to Chinese control; Canadian Prime Minister Jean Chrétien called Deng a "pivotal figure" in Chinese history. The Taiwan presidential office also sent its condolences, saying it longed for peace, cooperation, and prosperity. The Dalai Lama voiced regret.[33]

Legacy

"Deng Xiaoping, was one of the 20th century's greatest men. He ended Marxist dogma, releasing the energy of his long-suffering people whose nation had been raped by Western and Japanese imperialism, then ravaged by brutal civil wars and destructive Marxist policies. Deng's innocuous-sounding dictum, "it does not matter what color a cat is as long as it hunts mice", unleashed the greatest explosion of productivity and economic growth in history."— Eric Margolis [34]

"And in 1978 China had its first piece of great good luck in a long, long time--perhaps the first time some important chance broke right for China since the end of the Sung dynasty. China acquired as its paramount ruler one of the most devious and effective politicians of this or indeed any age, a man who was quite possibly the greatest human hero of the twentieth century: Deng Xiaoping. Deng sought to maintain the Communist Party oligarchy's control over China's politics while also seeking a better life for China's people, and he is guided by two principles: (i) be pragmatic ("what matters is not whether the cat is red or white, what matters is whether the cat catches mice), and (ii) be cautious ("cross the river by feeling for the stones at the bottom of the ford with your feet")"— J. Bradford DeLong [35]

Deng changed China from a country obsessed with mass political movements to a country focused on economic construction. In the process, Deng maintained the unrelenting political clout of the Communist Party of China, as evidenced by the 1989 Tiananmen Square Protests. Although some criticize Deng for his actions in 1989, China's significant economic growth in the 1980s and 1990s was largely credited to Deng's policies. Put into sharp contrast with Mikhail Gorbachev's glasnost and perestroika, Deng's socioeconomic model of a socialist market economy was a largely novel concept.

Deng Xiaoping's policies are among some of the most successful industrializations in human history, comparable to only the rapid industrialization of other East Asian countries, the Soviet Union and the home place of the industrial revolution itself, Britain. In a little over 30 years, his policies allowed China to move from the peasant society it once was to an industrial superpower with gross output second only to the United States. Despite controversial incidents such as the 4 June incident and the corruption of his son, Deng Xiaoping is largely remembered as a heroic and able leader.

The same policies, however, left a large number of issues unresolved. These issues, including unprofitable state-owned enterprises, regional imbalance, urban-rural wealth disparity and official corruption were exacerbated during Jiang's term (1993–2003). Although some areas and segments of society were notably better off than before, the re-emergence of significant inequality did little to legitimize the Communist Party's founding ideals, as the party faced increasing social unrest. Deng's emphasis in light industry, compounded with China's large population, created a large cheap labor market which became significant on the global stage. Favoring joint ventures over domestic industry, Deng allowed foreign capital to pour into the country. While some see these policies as a fast method to put China on par with the west, Chinese hard line communists criticize Deng for abandoning the Party's founding ideals and selling out China.

Deng was an able diplomat, and he was largely credited with the successes of China in foreign affairs. Deng's time as China's leader saw agreements signed to revert both Hong Kong and Macau to Chinese sovereignty. Deng's era, set under the backdrop of the Cold War, saw the best Sino-American relations in history. Yet during the last decade of the Cold War, he also oversaw the normalization of Sino-Soviet relationship. In the 1990s, this trend of improvement continued with Russia. Some Chinese nationalists assert, however, that Deng's foreign policy was one of appeasement, and past wrongs such as war crimes committed by Japan during the second Sino-Japanese War were forgotten to make way for economic partnership.

Memorials

When compared to the memorials of other former CCP leaders, those dedicated to Deng have been relatively low profile, in keeping with Deng's pragmatism. Deng's portrait, unlike that of Mao, has never been hung publicly anywhere in China. Likewise, he was cremated after death, as opposed to being embalmed like Mao.

There are a few public displays of Deng in the country. A bronze statue of Deng was erected on 14 November 2000, at the grand plaza of Lianhua Mountain Park (simplified Chinese: 莲花山公园; traditional Chinese: 蓮花山公園; pinyin: Liánhuāshān Gōngyuán) of Shenzhen. This statue is dedicated to Deng's role as a great planner and contributor to the development of the Shenzhen Special Economic Zone, starting in 1984. The statue is 6 metres (20 ft) high, with an additional 3.68-meter base. The statue shows Deng striding forward confidently. In addition, in many coastal areas and on the island province of Hainan, Deng is seen on large roadside billboards with messages emphasizing economic reform or his policy of One country, two systems.

Deng Xiaoping billboard in Shenzhen (Guangdong) |

Deng Xiaoping billboard in Qingdao (Shandong) |

Deng Xiaoping billboard in Dujiangyan (Sichuan) |

Deng Xiaoping billboard in Lijiang (Yunnan) |

Another bronze statue of Deng was dedicated 13 August 2004 in the city of Guang'an, Deng's hometown, in southwest China's Sichuan Province. The statue was erected to commemorate Deng's 100th birthday. The statue shows Deng, dressed casually, sitting on a chair and smiling. The Chinese characters for "Statue of Deng Xiaoping" are inscribed on the pedestal. The original calligraphy was written by Jiang, then Chairman of the Central Military Commission.[36]

In Bishkek, capital of the Republic of Kyrgyzstan, there is a six-lane boulevard, 25 metres (82 ft) wide and 3.5 kilometres (2 mi) long, the Deng Xiaoping Prospekt, which was dedicated on 18 June 1997. A two-meter high red granite monument stands at the east end of this route. The epigraph in memory of Deng is written in Chinese, Russian and Kirghiz.[37][38][39]

Sources

- "Fifth Plenary Session of 11th C.C.P. Central Chinese Committee", Beijing Review, No. 10 (10 March 1980), pp. 3–22, which describes the official Liu rehabilitation measures and good name restoration.

References

- ↑ Michael Yahuda: Deng Xiaoping: The Statesman

- ↑ China's leaders. Books.google.ca. http://books.google.ca/books?id=LUcNg8xYHtEC&pg=PA131&lpg=PA131&dq=#v=onepage&q=&f=false. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- ↑ China in the Era of Deng Xiaoping. Books.google.ca. http://books.google.ca/books?id=mDS0GW7FH_0C&pg=PA179&dq=#v=onepage&q=&f=false. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- ↑ "Luodai, a Hakkanese town in Sichuan Province". GOV.cn. 14 January 2008. http://www.gov.cn/english/2008-01/14/content_857292.htm. Retrieved 16 November 2009.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "The arrival of the Hakkas in Sichuan Province". Asiawind.com. 29 December 1997. http://www.asiawind.com/pub/forum/fhakka/mhonarc/msg00475.html. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- ↑ "Luodai, a Hakkanese town in Sichuan Province". GOV.cn. 2008-01-14. http://www.gov.cn/english/2008-01/14/content_857292.htm. Retrieved 14 May 2010.

- ↑ "Deng Xiaoping - Childhood". China.org.cn. http://www.china.org.cn/english/features/dengxiaoping/103417.htm. Retrieved 14 May 2010.

- ↑ Spence 1999, 310

- ↑ (fr) "Deng Xiaoping, l'enfance d'un chef". www.arte.tv. http://www.arte.tv/fr/Putin-Deng/1937950.html. Retrieved 14 May 2010.

- ↑ Stewart, Whitney, Deng Xiaoping: Leader in a Changing China, 2001

- ↑ (fr) http://www.persee.fr/web/revues/home/prescript/article/xxs_0294-1759_1988_num_20_1_2793

- ↑ http://www.timeshighereducation.co.uk/story.asp?storyCode=167965§ioncode=22

- ↑ Dr. Li Zhisui, The Private Life of Chairman Mao, Random House,1994

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 [Minqi Li. Socialism, capitalism, and class struggle: The Political economy of Modern china. Economic & Political Weekly, Dec. 2008]

- ↑ Deng Rong's Memoirs: Chpt 49

- ↑ Deng Rong's Memoirs: Chapter 53

- ↑ 1975-1976 and 1977-1980, Europa Publications (2002) "The People's Republic of Chine: Introductory Survey" The Europa World Year Book 2003 volume 1, (44th edition) Europa Publications, London, p. 1075, col. 1, ISBN 1-85743-227-4; and Bo, Zhiyue (2007) China's Elite Politics: Political Transition and Power Balancing World Scientific, Hackensack, New Jersey, p. 59, ISBN 981-270-041-2

- ↑ Cited by John Gittings in The Changing Face of China, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2005. ISBN 0-19-280612-2

- ↑ Cited by António Caeiro in Pela China Dentro (translated), Dom Quixote, Lisboa, 2004. ISBN 972-20-2696-8

- ↑ Dali Yang, Calamity and Reform in China, Stanford University Press, 1996

- ↑ Cited by Susan L. Shirk in The Political Logic of Economic Reform in China, University of California, Bekerley and Los Angeles, 1993. ISBN 0-520-07706-7

- ↑ FlorCruz, Jaime (19 December 2008) "Looking back over China's last 30 years" CNN

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Nathan, Andrew J. (January/February 2001). "The Tiananmen Papers". Foreign Affairs. http://www.foreignaffairs.org/20010101faessay4257-p0/andrew-j-nathan/the-tiananmen-papers.html.

- ↑ "Voices for Tiananmen Square: Beijing Spring and the Democracy Movement". Socialanarchism.org. 8 February 2006. http://www.socialanarchism.org/mod/magazine/display/32/index.php. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- ↑ Palmer, Bob (8 February 2006). Voices for Tiananmen Square: Beijing Spring and the Democracy Movement. Social Anarchism. 20.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 The Politics of China By Roderick MacFarquhar

- ↑ Deng Xiaoping's daughter defends his Tiananmen Square massacre decision. Taipei Times. 25 June 2007.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 The Legacy of Tiananmen By James A. R. Miles

- ↑ Miles, James (1997). The Legacy of Tiananmen: China in Disarray. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0472084517.

- ↑ "Los Angeles Times — Column One". Pqasb.pqarchiver.com. 9 September 2004. http://pqasb.pqarchiver.com/latimes/access/689588251.html?dids=689588251:689588251&FMT=ABS&FMTS=ABS:FT&type=current&date=Sep+9%2C+2004&author=Evelyn+Iritani&pub=Los+Angeles+Times&edition=&startpage=A.1&desc=COLUMN+ONE%3B+Great+Idea+but+Don%27t+Quote+Him%3B+Deng+Xiaoping%27s+famous+one-liner+started+China+on+the+way+to+capitalism.+The+only+problem+is+there%27s+no+proof+he+actually+said+it. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- ↑ Deng Xiaoping's Southern Tour: Elite Politics in Post-Tiananmen China Suisheng Zhao, Asian Survey © 1993 University of California Press

- ↑ CNN: China officially mourns Deng Xiaoping 24 February 1997

- ↑ CNN:World leaders praise Deng's economic legacy 24 February 1997

- ↑ Remembering China's Great Helmsman by Eric Margolis, The Huffington Post, 29 September 2009

- ↑ "DeLong Smackdown Watch: Dani Rodrik Strikes Back — Grasping Reality with All Six Feet". Delong.typepad.com. 15 July 2007. http://delong.typepad.com/sdj/2007/07/delong-smackdow.html. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- ↑ "China Daily article "Deng Xiaoping statue unveiled"". Chinadaily.com.cn. http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/english/doc/2004-08/14/content_365434.htm. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- ↑ Turkistan-Newsletter Volume: 97-1:13, 20 June 1997

- ↑ John Pomfret, In Its Own Neighborhood, China Emerges as a Leader Washington Post, 10/18/2001 as quoted in Taiwan Security Research

- ↑ John Pomfret, In Its Own Neighborhood, China Emerges as a Leader Washington Post, 10/18/2001 Preview, with option to buy, direct from Washington Post

Bibliographic sources

- Evans, Richard. Deng Xiaoping and the Making of Modern China

- Spence, Jonathan D. "A Road is Made." In The Search for Modern China. 310. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company, 1999

- Spence, Jonathan D. "Century's End." In The Search for Modern China. 725. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company, 1999

- Yang, Benjamin and Yang, Bingzhang. Deng: A Political Biography.M.E. Sharpe, 1998. ISBN 9781563247224

External links

- Free searchable biography of Deng Xiaoping at China Vitae

- Obituary, NY Times, 20 February 1997

- Selected Works of Deng Xiaoping

- Life of Deng Xiaoping

- China's former 'first family' (from CNN)

- China officially mourns Deng Xiaoping (from CNN)

- Deng's Free Market Nightmare (Maoist criticism)

- China 2002: Building socialism with Chinese characteristics (Communist Party USA)

- China Daily Biography

- Video

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Bo Yibo |

Minister of Finance of the People's Republic of China 1953 – 1954 |

Succeeded by Li Xiannian |

| Preceded by Huang Yongsheng |

Head of the People's Liberation Army General Staff Department 1975 – 1976 |

Succeeded by Himself in 1976 |

| Preceded by Himself in 1975 |

Head of the People's Liberation Army General Staff Department 1976 – 1980 |

Succeeded by Yang Dezhi |

| Preceded by Zhou Enlai |

Chairman of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference 1978—1983 |

Succeeded by Deng Yingchao |

| Preceded by None |

Chairman of the Central Military Commission of the People's Republic of China 1983 – 1990 |

Succeeded by Jiang Zemin |

| Party political offices | ||

| Preceded by Rao Shushi |

Head of the CPC Central Organization Department 1954 – 1956 |

Succeeded by An Ziwen |

| Preceded by Zhang Wentian in 1943 |

General Secretary of the Secretariat of the Communist Party 1956 – 1967 |

Succeeded by Hu Yaobang in 1980 |

| Preceded by Zhou Enlai, Kang Sheng, Li Desheng, Ye Jianying, Wang Hongwen |

Vice Chairman of the Communist Party of China Along with: Zhou Enlai, Kang Sheng, Li Desheng, Ye Jianying, Wang Hongwen 1975 – 1976 |

Succeeded by Li Desheng, Ye Jianying, Wang Hongwen |

| Preceded by Li Desheng, Ye Jianying |

Vice Chairman of the Communist Party of China Along with: Li Xiannian, Wang Dongxing, Chen Yun, Ye Jianying, Zhao Ziyang, Hua Guofeng 1977 – 1982 |

Succeeded by None |

| Preceded by Hua Guofeng |

Chairman of the CPC Central Military Commission 1981 – 1989 |

Succeeded by Jiang Zemin |

| Preceded by None |

Chairman of the CPC Central Advisory Commission 1982 – 1987 |

Succeeded by Chen Yun |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||